“To build real power, we need to use every tool that’s available.”

An interview with Ludovic Blain. Part 1.

An alarming and unsurprising article just showed up in my inbox. The title read “Here Are 56 Billionaires Backing Trump as He Promises to Slash Taxes for the Wealthy.”

Right. We all know this. The vast majority of the rich continue to line up behind right wing movements around the world, doing all they can to protect their wealth and power. This is the story we are familiar with. This is the traditional role of the owning class.

I want to tell a different story.

In this moment, as we face a determined MAGA coalition, with huge challenges on so many fronts, I want to learn from hopeful stories. I want to hear about messy, imperfect and real victories in building cross-class, multi-racial solidarity and power.

Ludovic Blain is one important part of the story I want to tell. He is a piece of the small but significant counter-narrative that I am lifting up through this project.

Over the last fifteen years, in his role as Executive Director of California Donor Table (CDT), Ludovic has led a set of wealthy progressives to move their money across tax statuses in alignment with a long-term, people of color centered, electoral power building1 (and power wielding) strategy, a strategy that has had real and significant wins.

Along with many others, he’s played a key role in turning Orange County blue, San Diego into a hub of progressive politics, building the political power of communities of color in the Inland Empire, and electing progressives to top offices in LA and the Bay Area. He is one of many who can claim a role in keeping the US House of Representatives out of Republican control in 2012, 2018, and hopefully this cycle as well.

I am delighted to get to share part one of this interview from last Fall. As usual, this interview has been edited for content and clarity.

Because I often find it useful in the longer articles I read, here is a summary of the topics covered below:

Ludovic’s class background and how it’s shaped his relationship to this work.

How he got involved in organizing the rich towards justice.

His mentors.

The importance of prioritizing impact over tax breaks.

The impact and successes of California Donor Table.

The dangers of ‘shiny object’ fundraising and the importance of funding infrastructure.

MG: Can you tell me a little bit about your class background and how it’s shaped your relationship to this work?

LB: First off, I often tell other people of color to not talk about their personal business in professional settings.

Why? Because usually on plenaries, panels and other presentations people of color have to prove our expertise by talking about our preferably traumatic personal experiences, whereas white people don’t have to prove themselves worthy to talk about whatever they want. White people are just seen as naturally smart. It's okay here, Mike, because you ask everybody for their personal story, including the rich white people you interview, but that’s a caveat I wanted to share.

I grew up in a low income family in the Bronx, eating yummy mac and cheese that my mom would make with government cheese. At the same time, I spent summers in Haiti with family who were relatively well off. I enjoyed that in Haiti I had people cooking my food and taking my dirty dishes. My class position depended on where I was getting off the plane.

My cross-class life as a kid helped ground me in the fact that class, money, and privilege are external forces and can change quickly. I learned early that class is a human condition, not an intrinsic part of your humanity. I learned that there are both wonderful things about having more money and personal downsides too.

Prince has got this beautiful quote, “money doesn't bring happiness, but it does fund the search.”

MG: How did you get involved in organizing the rich towards justice?

LB: In 1995, I got involved with the North Star Fund, the Funding Exchange affiliate in New York, as a community funding board member and then as a board member. North Star was where I first started learning about the dynamics between individual wealthy folks and organizers in philanthropy. I think almost all the donors I met were white women within a narrow age range. The activists were mostly people of color. You could figure out who was in which group by just looking around the room. Looking back, it was almost a caricature.

As I got more experience in philanthropy, I was increasingly frustrated with the decisions to fund ineffective, or at best distracting, work. I decided I could have more of an impact working directly with wealthy people rather than from within a public foundation.

In 2005 I moved out to California to join the New Progressive Coalition, funded by a wealthy couple. It was an online fundraising platform with the goal of helping organizations build a broader base of individual support, decentering high net worth donors, by providing an easier way for more middle class people to become passionate givers.

Right when the platform was starting to work, the donors pulled their money from the project because they’d decided to invest in a different strategy. Ironically, by defunding it, they proved the necessity for a giving platform that would decenter high net worth givers.

It was clear to me that we needed more people of color, more folks from working class backgrounds, more folks connected to immigrant communities, etcetera, in decision making positions in philanthropy to at least mitigate harm, if not make positive promotions. Representation doesn't fix all the problems of philanthropy– as African Americans say ‘not all skinfolk are kinfolk’– but diversifying the decision makers was and continues to be both necessary and insufficient.

In 2009, I was recruited by the founders of what has become the California Donor Table (CDT) to fill its first full time position. I became the first person of color, and first immigrant head of a state donor table2 in the country.

MG: Who have been your mentors in this work and what do you see as the lineage of the work that you're doing?

LB: One of my first philanthropic mentors was Betty Kapetanakis, who was the director of the North Star Fund when I was on the board. She was wonderful. She was patient. She was working on the power dynamics of donor organizing all the time. She was great about answering all my questions and explaining to me what was happening in the room. I’d say, “It was strange what happened in that meeting. Was that a rich person thing or a white people thing? And was there something that I did too?”

Later, Susan Sandler played the same role for me at major national donor events, orienting me to the dynamics in the room. She was grounded enough to be self-reflective, noticing and processing her own behavior [as a wealthy white woman] and asking me how I experienced it from my side. Listening to and learning from her helped me lead with more understanding and empathy.

Other mentors include philanthropic innovators like Susan’s husband Steve Phillips, Quinn and Wayne Jordan, Meg Gage and Lori Villarosa.

MG: What’s a lesson from your work with wealthy people that you want others to know and understand better?

LB: I have so many!

The biggest thing I've been at for more than 15 years is that I want wealthy donors to center outcomes rather than prioritizing c3 strategies because doing so gives them tax breaks. The only people who benefit from c3-centered giving are the donors. I want donors to invest long term in people of color power building across tax status.

The fact that wealthy donors have trained groups to prioritize c3 money requires interruption, especially when you’re dealing with individual donors who have much more flexibility than foundations. I feel 100% comfortable interrupting the c3 industrial complex that ignores the other tax statuses, organizations and strategies, for the sake of building the functioning multi-tax status movement we sorely need.

In progressive individual donor philanthropy I am the one to say, “Stop only funding c3’s! Fund c4s, PACs, IEs3, candidates etc. Stop centering the tax break of the donors!”

Adding more tax statuses to individual donor giving is complicated. But the reality is that, to build real power, we need to use every tool that’s available to us.

MG: What are you most proud of from your work organizing the rich?

LB: I'm most proud that through CDT, with a mix of individual donor, foundation and labor investment, we've been able to co-found and sustain a robust ecosystem of progressive people of color-centered power-building and power-wielding infrastructure4 around the state.

And we did that with a multi-racial group of donors that included wealthy mostly white people. CDT was founded by a group that consisted of 40% black men, 40% white women and 20% white men. We are certainly one of the donor networks with the lowest percentage of white male founders. People assume that, because we’ve always focused on communities of color, an overwhelming percentage of our donors must be people of color. But actually we have white donors who’ve been willing to center people of color power building over the long term, and continue to recruit and train more. I’m so proud of that.

At the start, rather than acting like we on the donor side knew how to do it, we acknowledged “Actually, you [the community groups] don't know how to do this at scale because we [donors] haven't learned how to give you the money to try. So we need to just jump together. And we are definitely going to make mistakes along the way! So let’s not worry about that, let’s learn from them. We’re stuck together in this state. So let’s go for it together.”

I’m proud of having more than a decade-long relationships with groups and with donors that have learned together along the way. No expectations of kumbaya. But some pretty fundamental lessons that have infused the Committee on States, dozens of state donor tables, Way to Win and a lot of other donor networks that have started up since. There’s been a real ripple effect from what we’ve pulled off.

Our long-term commitment to centering racial equity means we predate many of the flashy but ultimately short term racial equity ‘leaders’ that are newer to the scene, many of whom have already left. We’ve outlasted many in our commitment to this project. We’ve been doing it for so long that we are encountering challenges that only come from multi-decade efforts.

MG: Can you give me an example of power building that you're proud of?

LB: We were one of the earliest funders for power building groups in previously ignored regions like San Diego, Orange County, the Inland Empire, and Central Valley. The people of color-led progressive infrastructure we’ve helped to found and fund in each of those regions (like Communities for a New CA Action Fund, IE United, Engage SD, and OC Civic Engagement Table) played key roles in delivering progressive mayors, school boards, water boards, state legislators, all kinds of progressive policies, as well as Democratic House majorities over multiple election cycles. San Diego has turned from one of the most conservative parts of the state to one of the most progressive ones. And while this county is coastal, Lift Up Contra Costa Action, based in a previously ignored county in the bay Area, successfully re-elected its progressive District Attorney in 2022, the only place in the state where a liberal DA was re-elected.

Most wealthy California progressives live on the coast, but half the state does not. We've been able to build relationships between inland progressive leaders of color and our coastal transformational donors, and then use those interactions as practice for the groups to go to scale with more transactional state and national donors.

With our support, these inland POC groups, from ignored parts of the state, have been able to make their own individual and collaborative strategies, pushing, pulling and cajoling the parts of the state with more developed progressive infrastructure along the way. That has been wonderful to be part of.

MG: What’s one shift you’d like to see in how wealthy people are engaged by left movements?

LB: There’s a little too much focus on shiny objects, which are usually individuals. While I think organizations are nothing without individuals, the most charismatic people are sometimes necessary but are never sufficient. So we need to be institution focused.

Some donor groups have switched the focus from shiny white objects to shiny people of color objects. That might be one step forward, but it's a little bit of a step to the side because, first, donors have a track record of using up, burning out and then discarding shiny people of color. And then second, we actually need more movement infrastructure. We need COO [chief operating officer] functions in the movement, not just the inspirational Tedx/Black pastor types. So even while we're shifting to focus more on people of color, in some ways we're shifting away from white focused institutions to people of color individuals, and that is both a step forward and a step backwards.

I'm concerned because people of color have no shortage of charismatic folk. But focusing on those individuals and not infrastructure feels like something that's going to be as hard to fix as it has been to include more people of color in the first place.

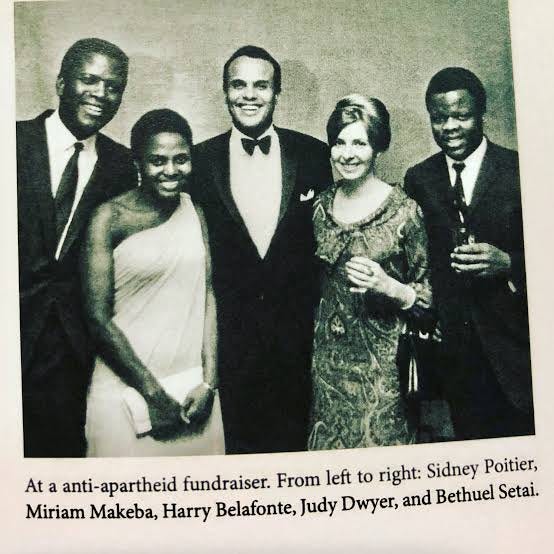

I wonder about the meetings on the Upper West Side when Harry Belafonte and Miriam Makeba were brought in to help with fundraisers for the Southern Freedom Rides. I mean, those were super charismatic folks.

Did Harry open with a song? What exactly was happening in that meeting? And how many of the wealthy people who came were there to meet the charismatic individuals like Harry or Miriam but left understanding and believing in, or at the very least robustly supporting, the institutions they were spotlighting?

I want to learn from those fundraising and donor organizing experiences. I want to understand how the money was raised and if the fundraisers thought their asks went well or if they felt like they left money on the table.

MG: Yes! We have a good hundred years of different experiments to learn from, at least, and I haven't found much written about them in an accessible way.

LB: Right. We might hear the story of the briefcase of cash going down to the South for the Freedom Rides, but I want to know how that money was raised. What was the agenda at that fundraiser? What were the relational networks used to get the money? Was it a Black hairdresser or funeral home owner, saying “Here's my fucking cash. It's not worth it being rich with all the racism”? Was it a white wealthy couple with a deep commitment to racial justice or were they just tickled to get a living room concert by Aretha Franklin? I want to know. I want to learn how those fundraisers thought about the relationship between charismatic individual fundraising vs institution building.

Infrastructure and institution building can seem boring. But actually the boring stuff is so crucial! Like if our movements are a car, mostly you want your car to have the boring stuff, like a well-functioning motor, brakes and headlights. A nice paint job is fine, but not the most important thing.

—------------

Thank you Ludovic!

This is just the start. Much more in Part 2.

Thank you to Lea Park (my mom!), Barni Qaasim, Ludovic Blain and Allison Harrison for your editing help.

‘Power building’ is a popular buzzword these days in my world. In the context of this interview, it means winning the power to govern and set policy through elections. ‘People of color power building’, a phrase used later in this interview, means building the electoral power of communities of color, to have their issues, opinions and values reflected in government and policy. In this case, it doesn’t mean just any values or opinions, but ones that align with a racial justice and progressive agenda.

A state donor table is an organization that brings together individual and institutional donors to move resources in alignment with a larger state based progressive power building agenda. (Wow. That’s a mouthful. Let me know if you have a more succinct definition.) Committee on States is the umbrella group for these state donor tables in the US.

IE stands for Independent Expenditure. An IE is money spent in support of or against a particular candidate, and not coordinated with a candidate’s campaign. More here.

‘Infrastructure’ is another popular social movement and philanthropy buzzword these days. I understand it to mean the year-round organizations and offices, staff and systems, databases and donuts (I couldn’t come up with a better alliteration) it takes to sustain long-term power building efforts.

The quote from Prince made me chuckle but it is spot-on. Good ideas need fuel, the dedication is part of it but you also need the money.

Michael, thank you for this interview! Ludovic is such an asset to donors and the philanthropy industry at large! The innovation of multi-entity funding is so crucial, and no one is talking about it! Glad to hear it loud, and plain!