There is much to be discussed and planned regarding what should be done in response to the current crises. Yes. Thanks to everyone who is involved in those efforts, including so many of you.

For Organize the Rich, this is another great day to learn from our elders and look back at the efforts of earlier generations.

Last month I posted an interview with movement elder Linda Burnham. We talked about the shifting terrain of money, class, organizational form and movement economics over the past 50+ years of the left.

Today, we return to those same topics with stories and reflections from historian, strategist, and writer Max Elbaum. Linda and Max are old friends and I love the chance to share these interviews close together.

I posted a short excerpt from this interview in October, and will share part one of our longer conversation today. I’ve really enjoyed getting to know Max over the last year. He is what my people call a “mensch,” a person of integrity and honor.

I talked to Max in early December 2023 at my kitchen table in Oakland, California. This transcript has been edited for content and clarity.

Max: I grew up middle class. My father owned a small business. My mother was a librarian. Our family followed a common trajectory for Eastern European Jews who emigrated to the US in the early 1900s: my grandparents, first generation immigrants, worked in the garment industry. The second generation climbed up the class ladder a notch to become teachers, social workers, and small business owners. And the third generation was supposed to go on to become doctors or lawyers–

Mike: – or Communist organizers? [laughs]

Max: – Yeah, I got off that train [of upward mobility] and went in a different direction.

My parents said, ”You want to be a communist!? Can't you be a communist doctor or a communist lawyer or a communist college professor?” They didn't like communism particularly much, but what they really didn't like was me not climbing the professional ladder.

Mike: [Laughing] I love that story.

Max: We tussled about it for awhile but eventually they learned to live with my choice. I was a student activist but did graduate college, then joined many other radicals in my generation in getting a working class job and living in a working class community in order to organize workers for the revolution.

In the mid-1970s I was pressed to become a full-time “internal” cadre doing mostly writing and editing. I did that kind of work for the next 20 years, for the first 15 years earning subsistence wages as part of a communist organization, the last five earning a bit more - I think I got up to $20K a year - editing a more ecumenical radical publication.

In 1995 I left that role so a younger person could take the paid position at the magazine I worked for at the time. I got an office job in the records management department of a company that leased railroad cars and airplanes and went back to my roots in doing my political activism as a volunteer in my non-working hours. I retired in 2019 just before the pandemic.

Mike: Thanks for walking through your class background and work life. The details are helpful as a way to understand the movement economics of the times.

As far as I’ve found, formalized efforts to organize the progressive rich started in earnest in the 1970’s with projects like the Vanguard Public Foundation, Haymarket People’s Fund, and the Conference on National Priorities.

What are some of the broader trends in the left in the 70’s that are important to understand, so I can put those efforts into context? Both around the left’s strategy and your experience of its relationship to wealthy progressives.

Max: In the early to mid-1970s, the mass upsurge that had been a feature of US politics since 1955 turned toward an ebb. The initiative was starting to shift from the movements for social justice to the right wing backlash which by the end of that decade brought Ronald Reagan to the White House.

As this process unfolded, some individuals and groups who had participated in the protests and direct actions of the radical ‘60s shifted their strategies. With the Voting Rights Act still in force and a large base of people who had progressive sentiments ready to vote, if not to go into the streets, there were openings for social justice advocates to get elected at the local, state and even national level. Policy expertise and skills at working the legislative system took on greater importance in the fight for specific reforms.

There was a general need for projects and institutions that functioned with a larger proportion of staff to volunteer energy than had been the case when there was energy welling up from below. And there were people who had the resources to support those kinds of institutions. A layer of people, who had been radicalized in the 1960s, and who had access to family money, had come into being. This was the context in which those community funds, starting with initiatives like the Vanguard Public Foundation, took shape.

The current on the left I was a part of recognized that we were going into an ebb period. But we felt it would be relatively short-lived. We thought that more and more countries in what we then called the Third World and now is generally termed the Global South would break free of the US-led world capitalist system. We believed that the US ruling class would face a serious profit squeeze, and that the resulting attacks on the US working class’ standard of living would produce another upsurge that would be both more radical than the 1960s and more rooted in the multi-racial working class.

We saw our task as embedding ourselves in the working class and building the kind of combative political party that would be able to exercise leadership in a period of intense, perhaps even insurrectionary, class struggle. It was an ultra-left assessment, but it seemed plausible to a lot of us at the time.

So a lot of young folks from middle class backgrounds moved to working class neighborhoods; mostly to get jobs in factories, hospitals, sweatshops and so on, with some focused on non-workplace organizing of youth or bringing their politics to existing community organizations. A lot of young people from working class backgrounds took this course too.

The ‘60s were the first time large numbers of working class youth and youth of color went to college, and many were radicalized and decided to return to organize the communities from which they sprang. There were rich kids doing this too; not a large number, but some. This ‘organize the working class” trend was taken up under one or another ideological banner within Marxism or Marxism-Leninism.

The economy at the time made taking this course easier than it is for young people today. It was before de-industrialization and it was possible to get a blue-collar job. Union density was higher so you could get a job in a unionized workplace. And the cost of living, especially of housing, was much less than today. Salaries went a lot further then, and twenty-somethings without kids could live cheaply, or crash on couches like SNCC and SDS activists before us. A couple of folks working full-time could support someone organizing full-time, and also pay substantial dues to whatever radical group they were members of. Like churches, the groups that aspired to become a revolutionary party expected members to tithe – anywhere from five to twenty percent of their income. The economics were totally different back then.

Our wing of the left never considered focusing on rich people and I don’t know of any other current in the radical left of the time that did either. When wealthy folks joined us, we integrated them [into our project of organizing the working class] – some became dedicated cadre. Many kept their wealth quiet, maybe telling leadership privately. We'd handle their financial contributions differently but otherwise treat them like anyone else.

Mike: How and where did you encounter wealthy progressives and leftists during the 70’s?

Max: I can remember encountering three different people who had money between the early 1970s and the end of the 1980s.

One of them was an older person who had been in the Communist Party, and when they heard about Line of March, the party group I was in, they liked our politics better. They moved into our orbit and gave us around $30,000, which seemed like a fortune in the late 1970s.1

The second person, who I never met but knew of indirectly, was more in the world of institutional fundraising. She had a personal friendship with a Line of March leader and gave us two or maybe three $10,000 donations over the group’s 15 year existence. That relationship was limited to her friendship with that particular individual….more of a classic ‘financial angel’ situation.

The third person was a rank-and-file cadre who was younger than me, who funded our building’s down payment – money she got back when we disbanded and sold it. I don’t think she would be considered rich by today’s standards, but she had a high-paying job, was both frugal and generous, and I think had inherited money in the high five-figures. She told the leadership she had resources and was willing to contribute more than regular dues payments. For perspective, I earned just $450 monthly [$2,428 in today’s dollars] working full-time for Line of March from 1977 until we disbanded around 1989-90. All of those who like me were assigned to work full-time for the organization earned subsistence wages and the vast majority of the members - 90 to 95% - had no expectation of being paid for their political work.

Mike: In your experience, how was left organizing funded before the rise of nonprofits and institutional philanthropy in the 70’s and 80’s?

Max: From what I know, there were four funding sources:

1. Dues-paying and donating working and middle-class members.

2. Income from the sale of subscriptions to the newspaper and political journal, and from the sale of individual copies of various pamphlets and books published by the organization

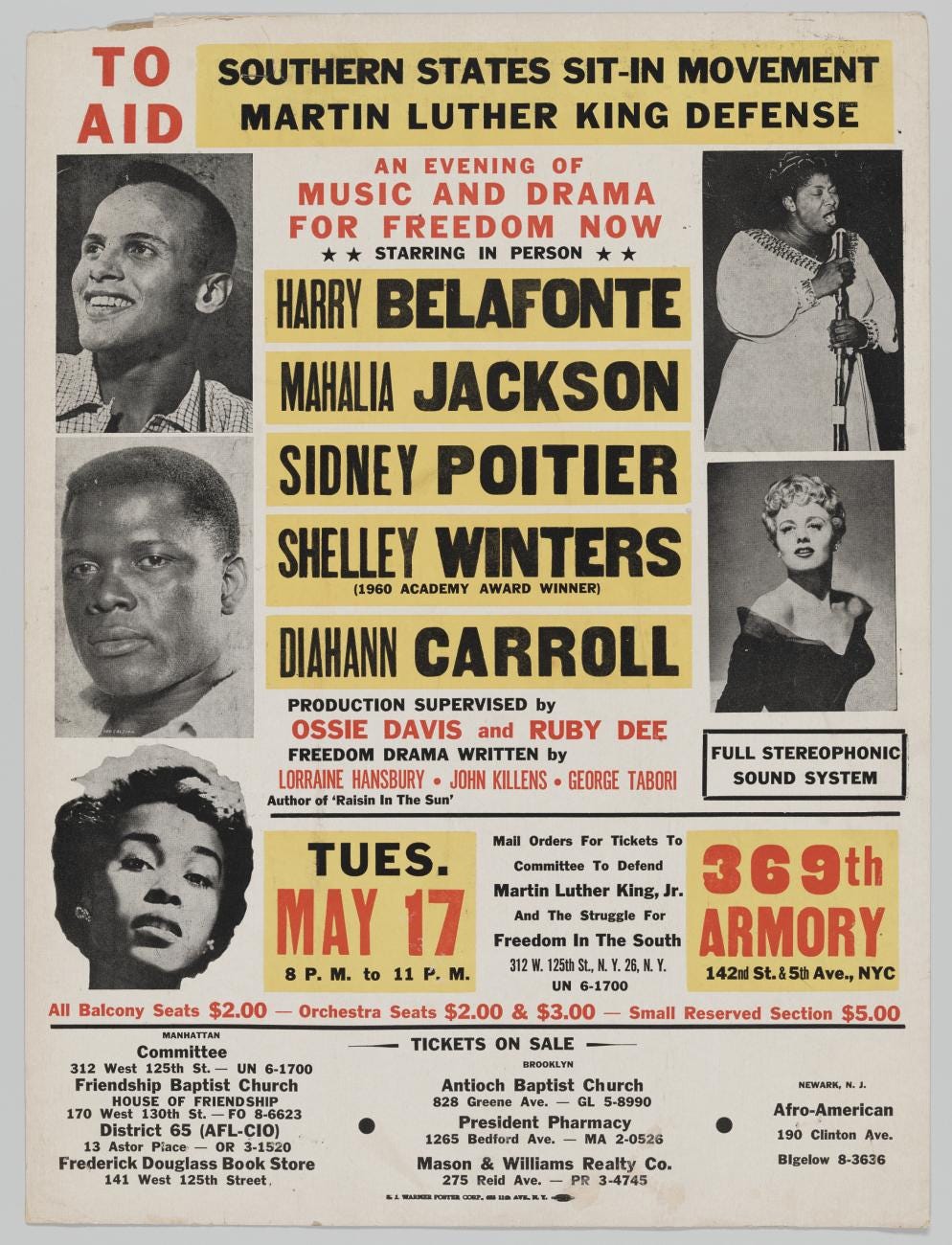

3. Special fundraising often through artist-led benefits. In the 60s, especially during the civil rights movement, many artists and entertainers gave personal funds, but more often did benefits. Harry Belafonte is the classic example, but you also had Barbara Dane, Holly Near, Jane Fonda’s FTA [Fuck the Army] tour. Even Bob Dylan did a benefit or two. These cultural workers served two goals: popularizing left ideas–and fundraising.

4. Financial angels. These were individuals like those described above who had more resources and were willing to make substantial donations to the organization.2

But for all of those groups by far the main source of income was the first three categories noted above, especially the first category, member dues. This was the same for the Communist Party and other groups of the “Old Left.” Each one had a few wealthy supporters, but the overwhelming source of income was dues from working class (and some middle class) members who went to work, organized at their job or in the community, and supported the party financially.

Mike: Thank you for that. It’s a helpful breakdown.

You’ve talked about how your part of the left focused on "going to the working class" and organizing in working class communities, even if those were not the communities you had grown up in. I wonder how you see that now?

Max: I still think that’s a good - even important - direction to go in. I think the working class broadly defined has to be the main force (not the only force, but the main one) if the project of deeply democratizing this country and going beyond capitalism is going to succeed. And I don’t see how that happens unless there are radicals who share the conditions of working class life organizing and activating their co-workers and neighbors. The majority of those people I believe will be people who come from the working class itself and adopt radical politics, but part of the process is people from the middle-classes who are radicalized making the decision to “go to the working class.”

Of course there are lots of complexities involved in doing that successfully. If people of any background function as missionaries who think they have “the word,” that they have lots to teach and nothing to learn, - well, that will never work. But as a general orientation, yes, the left has to embed itself in the working class - which is multi-racial and gender-inclusive, full of people with different religious beliefs and abilities/disabilities, and so on - or it will not become a powerful force in US society.

Mike: As you look back, do you think ‘class guilt’ was part of those decisions to go organize in the working class? Did anyone talk about the potential for that? Because I see this today – class privileged leftists who would prefer to hide their connection to wealth or wealthy people, and spend most of their time in the working class. It’s a trend I often push against.3

Max: That's interesting. We did not talk about class guilt per se. We did talk about class privilege, racial privilege and gender privilege. The line in my group was “Everybody who enters the movement has some baggage. They enter the movement because they want to do something progressive. So they're basically good people. You take up a struggle with someone if they act badly or mistreat others on the basis of elitism or of some other prejudice, and you believe that they can change their behavior because they want to strengthen the movement.”

If someone joined the party who was better off, we criticized them if they acted badly – talked down to somebody, the interpersonal dynamics, what we now call micro-aggressions. But we didn't criticize them on the basis of being rich.

We studied the Yokinen trial. Yokinen was a Finnish communist in Harlem who turned Black people away from a dance at the Finnish Workers Club. So the Communist Party did a community trial on him as a rectification, or what we'd call today restorative justice. It was a big hit in Harlem, and was publicized across the country as a model of how you deal with prejudice. The party was saying, “This was wrong. It was chauvinism. When our members act out, we deal with it.” He participated fully, he committed to changing his attitudes and actions, he wasn't demonized as a person.

“Cure the disease to save the patient” was the Maoist way of phrasing that approach. The idea was that once people joined the movement, they should be valued and their contributions respected. The “new communist” groups didn’t always live up to that in practice, these organizations were generally too top down and too interested in maintaining ideological conformity to have a stellar record on this front. And a few did fall into really bad patterns of cultism and abuse. But that kind of thing was not the norm.

We also read Lenin. His line was “Within the party, all characteristics other than politics are moot.” We took this to mean that in internal debates we didn’t judge a position by the class, racial or gender status/background of the person offering that opinion. As noted we took up struggles against behaviors that were racist, sexist, class-biased or reflected some other prejudice. But as to discussing political strategies and tactics or theoretical views, it was important to deal with them on their merits.

Mike: Having grown up in the Bay Area, my stereotype of who would be in a communist organization, is an older white guy from Berkeley wearing a beret with lots of pins on it. Given that image in my mind, I want to ask, was Line of March multiracial?

Max: Two of the three top leaders were Filipino. Thirty to 40% of the membership and a higher percentage of the leadership was people of color. That was about the same as the October League. The Revolutionary Communist Party (RCP) was whiter. With both of those, the main leader was white. The League of Revolutionary Struggle was 80% people of color, top leadership was mostly people of color. The Communist Labor Party was led by Nelson Peery, a Black man, and the Communist Workers Party’s top leader was Jerry Tung, an Asian man.

Mike: I know this isn't the primary focus of your work, but do you have thoughts on the strengths and challenges of how the left currently engages wealthy people ?

Max: I take your question to be referring mainly to that part of the left that is organized into 501c3s, heavily reliant on philanthropy for its income, is organized on the Governing Board/Empowered Executive Director (or Co-Directors) model, with most work done by paid staff.4

What I see in these groups is a tendency to write grants to match what they perceive to be funders' interests, then try to work around the constraints. Some of those groups have a coherent theory of change and political strategy, others don’t. But what I don’t see enough is even groups that have a clear strategy putting that forward to the funders in the same way they talk about it internally or with those they are trying to organize. I don’t see keeping quiet about a group’s strategy as an approach that can win over the long haul.5

Avoiding deep political discussions with rich supporters for fear of losing funding is shortsighted. If there's a real disconnect, it'll surface eventually – might as well get it out in the open. Sure, you need to consider each person's situation, but start by treating them like any other serious political person. Try to convince them of your politics, just like you would anyone else.

I was lucky that I came up in a time when large numbers of people with very diverse views were opposing the Vietnam War, fighting racism, and searching for a path to deep-going change. I was forced to learn how to function in coalitions and spaces where there were many political disagreements.

I learned that you don’t give a speech with your entire political outlook every time you open your mouth. But if you're in a setting where someone really wants to know what you think; if someone is open to becoming a supporter of your work or taking some of the work on themselves, you have to treat them strategically. You tell them what you think, what you have firm opinions about and what you don’t. No dissembling.6

Mike: You make it sound so simple!

Max: The framework is simple. Carrying it out in the rough and tumble of the real world is not. And I get it that folks who don’t have or come from money and are in projects that need money can feel awkward, stressed or just plain uncomfortable when talking to people who have resources.

I felt awkward the first time I knowingly talked to an audience of wealthy people. It was on a zoom call Solidaire organized before the 2022 midterms. Linda Burnham, Maria Poblet and I had edited the book Power Concedes Nothing: How Grassroots Organizing Wins Elections and were presenting on it for their membership. Awkwardness aside, I didn't say anything different than anywhere else I present. No one told me I should do anything different, so I defaulted to my usual practice.

Mike: How did you get connected to Solidaire in the first place and end up speaking from the stage as part of the opening plenary [of their 2023 Membership Gathering]?

Max: I was totally shocked when I got invited. I imagine it was because I co-edited the Power Concedes Nothing book and it was well-received by the Solidaire staff and membership. And perhaps some people had read my other writings for Convergence Magazine.

Mike: So many leaders in left and progressive organizations are trying to figure out how to speak to wealthy people in a way that engages us and turns us into donors. I like that you center the idea that we should speak to everyone as a serious political thinker first and foremost. I think it’s easier said than done, especially given the classism we’ve [the rich] learned that tells us we know best. And it’s an approach that has a lot of integrity, which is a wonderful contradiction to the general culture of coddling or harsh critique that rich people are used to.

THE END (of Part 1)

More to come in Part 2, where my conversation with Max explores how the left has related to electoral politics from the ‘70s to today.

Thank you for reading!

If you liked this post or engaged with it, click the heart below to boost it in the Substack algorithm, or better yet, restack it on Substack Notes.

And thank you to Allison Harrison, who edited and contributed to this piece.

$30,000 in 1979 is $135,928 in today’s dollars.

Do you have stories of wealthy benefactors of the left and liberation movements that you think should be more well-known? I’d love to learn about them. Comment below or email me.

I was taught that to be an effective organizer of the rich, I need to have one foot solidly in owning class communities and one foot solidly in working class led movements and communities. Easier said than done, and what I aspire to in this work.

I LOVE that Max distinguishes between the different organizational forms that left organizing can take, getting explicit about which version he is referring to. Whether an organization is a foundation dependent c3 or a dues funded labor union or a mid-to-large donor funded c4 makes a big difference to the culture, tendencies and power that they have.

Max’s comment here reminds me of this recent piece by Nina Luo in The Nation, “Left organizing is in crisis. Philanthropy is a major reason why.”

In case, like me, you have no idea what ‘dissembling’ means, I looked it up! The definition is to “conceal one's true motives, feelings, or beliefs.”