"Organizing is a skill like anything else. You can learn it."

Interview with Rajasvini Bhansali

I met Vini at a Making Money Make Change retreat at least a decade ago. At the time, she was the Executive Director of IDEX, now Thousand Currents, a 38-year old international grantmaker funding grassroots groups and movements in the Global South.

I remember she was joining a Shabbat led by the Jewish attendees (of which I was one) at the conference. She was outspoken about loving Jews and Shabbat and being glad to be invited to participate. I’m not used to Leftists openly loving Jews, and I fell in love immediately. She was warm and kind and funny, and as I got to know her, it quickly became clear what a badass organizer, visionary, and strategist she was (and is).

Since then, I’ve always tried to stay close to Vini and say yes to any asks she makes of me. I worked for Vini as a Development Consultant with Thousand Currents in the months before my son was born, and when she became the Executive Director of Solidaire in 2018, I was thrilled and knew I wanted to get more involved.

Vini is a central leader in the US Left’s efforts to organize the rich. Her leadership at Solidaire has been crucial to its current success as one of the most interesting experiments we have going. Solidaire has become a thriving intergenerational network whose members are both institutions, represented largely by middle-class philanthropy professionals, and individual wealthy people. It started off with a focus on rapid response funding and has become a key provider of multi-year general operating dollars for frontline intersectional movements. More than most, it is well nested within Left movements. What she shares below is hard-earned wisdom from her many years of experience.

As always, this interview is loosely based on these questions, modified from ones developed by Linda Burnham, and has been edited for content and clarity. Vini and I talked in her living room on June 12, 2023.

MG: “Organizing” is a popular buzzword these days, with a lot of different definitions. I'm using it; many others are too. What does “organizing” and “organize the rich” mean to you?

VB: Organizing is helping people believe in their own agency to change the world.

Organizing works when people believe in their own capacity to be an actor, be a changemaker, and develop the skills they need to do it.

The opposite of organizing is when a rich person is like, “I'll write a check, but don't talk to me and don't ask me to talk to anyone else.” A wealthy person with an organizing mindset says, “Yeah, of course, I'm going to bring my resources to this, but I'll also bring my friends and my uncle who's connected to this terrible hedge fund that we can help divest from the prison industry.”

Organizing means looking at the whole of your life and all the resources at play and bringing them to bear for a collective change agenda.

I used to think of organizing the rich as a lot easier than it actually is.

In the Global South movements I got to know at Thousand Currents, everybody is seen as organizable all the time. I had that mindset. Now working more in the US, with entrenched wealth, and all the patterns of white supremacy and inequality, I'm understanding the immense challenge we face in a deeper way.

Organizing the rich is harder work than we give it credit for, which is why Solidaire is not going to be enough and Resource Generation is not going to be enough.

We have to have an entire ecosystem of people that can speak to and organize different subsets of the wealthy. Donors of Color Network can reach people Solidaire won't. Resource Generation reaches young wealthy people that Solidaire can develop further. We need all of us. And we all need to have a strategic division of labor, so we can organize a mass base.

There is so much disorganized wealth: wealthy people who are not connected to anything and don't want to be because they don't see the value in it.

Somebody needs to get all these unorganized wealthy people to understand the value of being part of something bigger than themselves. We know that there are 725 or so billionaires in this country right now, so 350 Solidaire members [their current number of members] is just a start.

How many of these billionaires are part of something that we recognize as connected to progressive movements? Not many.

How many moderate billionaires get swept into the Right? Because the Right seems to create magnetic conditions of belonging?

Our task is huge and we have to be better at it.

MG: How did you come to participate in organizing wealthy people for social justice?

VB: I came to it from being a fundraiser. I spent a lot of years raising money from wealthy people and realized that there were many indignities, large and small, involved in the process. It all made me wonder what frontline organizers were going through to be able to get the resources they deserve for their work.

The earliest memory I have of fundraising indignities was when I used to volunteer for an organization called the Political Asylum Project of Austin. It was just impossible to talk to the wealthy donors about asylum and refugee seekers without falling into saviorism. It just didn’t have an impact if we talked to our big donors about giving because it was the right thing to do or a movement that really deserved their solidarity.

The whole asylum, refugee, and immigrant rights movement learned to talk in a way that made the work about “the good immigrants” versus “the bad immigrants,” the ones that had no choice in their circumstances versus those that chose to illegally migrate. There were all these polarities that were created mostly to raise money and speak to what organizations learned wealthy people wanted to hear.

I became the Executive Director at IDEX [now Thousand Currents] very young, at 31 years of age. I remember one meeting early on where I was sitting across from this white wealthy donor who said to me, “I like this work. I believe in this work, but for some reason, I can't trust you, so I am not going to renew my funding.”

Even though I had done a lifetime of racial justice work, I remember being floored. I couldn’t get out of bed for two days. I was so hurt and wounded by that. I understand that what he meant was that I was too brown, too young, too different — that somehow my accented English made it hard to believe me. Coming out of that experience, I remember thinking, “If this is how we plan to raise resources for Global South solidarity, we are not going to be successful because our donors do not see themselves in this work.”

MG: What is your class background? How has it shaped your relationship to this work, organizing the rich?

VB: I have a mixed class background. I grew up lower middle class, but with a lot of privileges because my dad worked in the civil service in India and rose up through the ranks. We had access to health, education, and housing benefits that weren't related to wealth, that were related to public service in India. When I came to the US, the idea that you have to twist yourself into a pretzel for what should be a public good was very new to me.

Now, I'm squarely upper middle class, both by way of my job, but also because my extended family's class position changed as my brothers made money working in finance. We now have these nuanced conversations within our family about what it means to have more than our relatives and what it means to support a larger extended community. All these questions about class and wealth have gone from being external to my experience to becoming internal to my family and life.

MG: Who are your mentors in this work?

VB: Two of my most important mentors have been Paul Strasburg and Mutombo M’Panya, the two co-founders of IDEX, now Thousand Currents. They modeled values of deep humility and deep learning in relationship with whoever you consider your grantee partners, whoever you are in a position to resource financially. They embodied this understanding that you're not just donating out of a sense of charity, but you're really doing it for you.

This is the fundamental tenet of solidarity, especially between the Global North and Global South. You're not trying to help and save somebody else, you're actually doing this act of giving because it frees you and teaches you some other way of being with the resources in your control. The word that Mutombo always uses is being an “honest broker” between the North and the South. And it applies to solidarity in all situations. It’s important to be honest about what we're learning and about how wealth accumulation is based on imperialism, exploitation, and more.

The other mentors I often think about are Jorge Santiago and María Estela Barco Huerta from DESMI in Chiapas [Mexico]. I was at the launch of an experiment, the Buen Vivir Fund. We had brought together all these impact investors with Global Southern leaders. At the meeting, Jorge said, “Let's get out of this dichotomy of investor and investee. The investors in this room, primarily white, primarily from the Global North, are bringing financial capital to the table. Those of us, quote unquote recipients, are bringing intellectual capital and political capital to the table. We will be far more powerful together if we're in reciprocity, if we see each other as co-investors.”

You can apply that to the idea of co-conspirators, of reciprocal lateral relationships, not this classic philanthropy “power over” dynamic. We are not just in a relationship where “you give me money; I'm subservient and subordinate to you,” or “you get to enact your dreams for what you want in the world by making me your proxy; I get to come to you with the begging bowl.” We need to be in an exchange and understand the different forms of “capital” in circulation.

Lately, I have been blessed to learn so much from Solidaire’s own Elder in Residence, Linda Burnham, and her massive strategic and power-building contributions to the field through Power Concedes Nothing: How Grassroots Organizing Wins Elections and Project2050. I have also been so fortunate lately to learn at the feet of elder and scholar Dr. Henrietta Mann, who embodies the kind of principled brilliance and tenderhearted clarity that teaches me how to be utterly human at all times.

My mentors have taught me how to do this work with a lot of joy and love, and a lot of centering, not on bitterness and hard political analysis, but on a deep belief in people's humanity and potential for transformation.

MG: What are some of the things you're most proud of in this work of organizing the rich?

VB: I'm really proud about who the “we” is becoming at Solidaire. Our membership is transforming. It’s now around 75% people with wealth and 25% people who are organizing wealth but are not themselves rich. More and more, we are a true cross-class network of people who move money to frontline movements. We are not only organizing the rich but also (dis) organizing philanthropy and the systems by which wealth moves to social movements.

I've been on these regional tours in the last month, meeting with members around the country. It's been so fun to watch people talk about Solidaire as theirs. I’m proud of the sense of ownership and belonging I’m seeing — the felt sense that this is a collective power-building initiative that each of our members is giving their life and resources to.

The other part I feel really proud of is how much money we've moved.

I feel proud of how we've been seen as a trusted partner, and this is demonstrated by how easefully folks on the front line can access Solidaire. We are not practicing philanthropy in that really old school way, where it is “us” and “them.”

Our staff come out of frontline movements. We are rightfully seen as part of multiracial movements, and because of that, our boundaries are much more porous than most philanthropic organizations. We're constantly learning, and we're also constantly being asked to contribute in ways other than grantmaking dollars. Sometimes we’re asked for accompaniment in ways that allow us to flex positional power, and sometimes we are a shoulder to cry on. That feels like a big honor.

The Solidaire I started working at in 2018 was known for and great at rapid response funding, especially in moments of movement emergence and crises.1 We always have been excellent at bringing members together, but we were less nuanced around what it means to be in partnership with cross-class, multiracial movements. That aspect of our work is both new and deeply needed right now.

MG: Are there particular ideas that you want future generations of leftists to know about organizing the rich that you hold or that you would like to lift up in this conversation?

VB: There's so many.

The biggest assumption for me that has gotten tested in my five years at Solidaire is the idea that wealthy people have to always be convinced to support Left movements. That idea has really gotten blown out of my consciousness. Through Solidaire, I have met wealthy folks with a long and vital history of involvement in and support for all sorts of liberation movements and progressive and Left movement building.

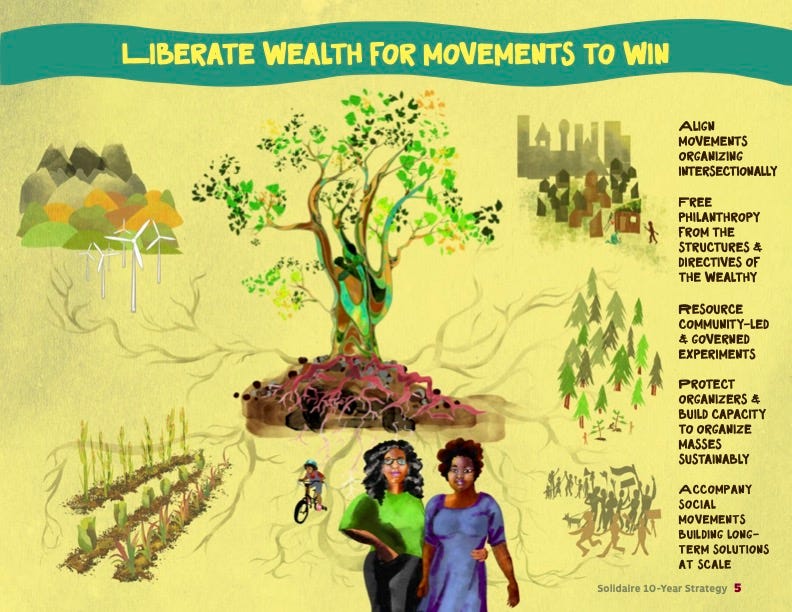

In Solidaire’s new 10-year strategy, we write a lot about the protagonism of wealthy donors. As a student of social movements and as a student of history, I strongly believe that people of all class backgrounds have to be involved in movement building.

What we often think of as a lack of protagonism from wealthy people in Left movements is often a kind of shadow protagonism. When wealthy people aren't explicitly engaged and given clear direction, they're often involved in sideways ways that cause more harm than good. That's why, where there is initiative from the rich towards progressive social movements, where there is motivation, where there's inspiration, it makes sense to purposefully develop their leadership and give them clear roles and work to do.

I firmly believe that the protagonism of everyone, including rich folks, actually matters — it’s not only about getting in line behind working-class movements, though that is vital. It’s about each of us actually bringing our own influence, agency, power, and resources to the table. This full-bodied protagonism is what rich folks need to move from guilt- and shame-driven redistribution to a lasting role in systems change. US capitalism, in my humble opinion, will not change without strategic action from the wealthy and those with access to wealth.

Another important notion that I hold dear is that organizing is a skill like anything else. You can learn it. It can be taught.

What I feel progressives with access to wealth in this country don't get enough of are places to develop organizing skills, especially around the family systems and institutions that they can uniquely influence. Left and progressive donor networks are important because that's where they get to practice.

My wish may be that every one of our members arrives perfectly baked and does the exact right thing, but that feeling is actually just about control. That's not how real humans work.

If we can create an alignment of values and an alignment of purpose, then wealthy people will also join the struggle for collective liberation. I've seen it with our own membership, where people come in really green, really fearful. They have never had to, given their wealthy background, work with people different from them.

Then they come into an organization like Solidaire, and over time, with practice and skill building and enough experiments, they begin to learn how to work with other people. Check their own ego, check their own assumptions, try to work on a project together, get their hands dirty, make some mistakes, learn hard lessons, and then try again.

That's how I became an organizer. I didn't go to college for it. I was deployed to door knock, to talk to people, to start initiatives, to bring others along. And with enough community work and enough feedback, we begin to get better at it. I mean, I’m still learning.

If you look at the history of philanthropy in particular, most trustees have been able to make decisions entirely in isolation, on their own, without any accountability. Wealthy people can have hundreds of staff that pretzel around just to try to give them the perfect case for support so they won't retract their funding.

This is how mainstream philanthropy still operates. A trustee goes to a cocktail party, listens to an idea they like, and makes a new decision about their grantmaking. Suddenly, the flow of resources for their work, their foundation, their grantees changes overnight.

There's not enough movement- and values-aligned mechanisms for peer accountability, peer support, and peer learning at high levels of wealth. And without that, I don't see how we ever get out of these unhelpful and destructive patterns.

MG: What do you see as the current strengths and weaknesses of the Left's organizing of the rich?

VB: The greatest strength is that, in the US context, more and more movement formations are being completely honest about the money, long-term support, and engagement they need from donors and foundations.

We now have mass based, working class-led organizations that have the capacity to engage and develop the wealthy. We're seeing an understanding that if we want this multiracial, pluralistic, democratic future, we have to engage across class and the wealthy have to be a part of it. They have to have the right roles within this larger movement. I see greater consciousness of that and clarity around that than I did 20 years ago.

The weakness is that we are up against so much and the rich have to be less precious. We’ve got to lose the service orientation of “my needs are more important than everything else, and my preferences are more important than everything else.” That has got to change.

The individualistic attitude that, “I want to do social change the same way I want to build a new company” — that has to change.

It can't be a transaction. Movement formations do not exist to serve the unique needs of every wealthy person, and it would help everyone if the rich would spend less time looking for a reason not to trust the groups they’re trying to support. I’d love to see more wealthy people understand how the long arc of change happens and how movements evolve, and be okay and accepting of the messy stuff of social transformation.

Things like matched funding are often part of the problem. “If you can show me that you can do it, then I can release the money.”2 It is one of the ways in which the directives of the wealthy are divisive and create more problems than solutions.

It's one thing to be at a party with your friends and talk about how “we're so different than the Koch brothers.” It's another thing to really examine, “Are we different? How am I behaving? How am I showing up? How am I in authentic relationship and partnership with the groups I support? Am I listening, or am I glazing over when a brown person is talking to me … because in my mind I'm formulating my response rather than deeply listening.”

The second very specific weakness is our desire to find a charismatic, singular leader that will provide “the solution.”

Not all charismatic leaders are accountably involved in social movements; its easier to invest in entrepreneurs who are really good at hustling people into believing that their vision of the perfect widget is going to change the world.

I want the wealthy to have more nuance.

Social change does not happen on the backs of a singular, charismatic leader. Many many good people are involved in the nuanced and complex work of change.

That's why I resist the notion even for myself. I appreciate the love I get from our membership. I really do appreciate my own leadership. I believe in leadership. I believe well-led networks are important for this time in the world. And I do nothing alone. It's an entire team of very hardworking people that make Solidaire’s work come to life.

MG: If you could identify two priorities for lefty rich people organizing over the next 5-15 years, what would it be?

VB: This is good timing. Solidaire just came out with our 10-year strategy. And I feel like our strategy is not just for Solidaire; it’s for the ecosystem of social change and movement funding. Solidaire is just the place where I can shape this work most directly.

I very much hope that we focus on organizing, organizing, organizing — which means, providing the training and support for our members, whether middle-class professionals or wealthy people, to free up more of their resources, from their workplaces, families, or their own bank accounts.

That needs to be our singular focus and truly organize — not preach at, not yell at.

My second priority would be to more fully accompany social movements, movements that build a power base of people who have not had power in this system. We still haven't nailed that.

We've got to do that for the next 10 years at the bare minimum, to start to see some of our weakened sectors actually have a chance to craft policy, change laws, and govern.

That's long-term work, and often wealthy donors and funders have real short-term metrics. I want that to change. I want us all to align behind a longer-term strategy and change agenda.

MG: What is your 150-year vision of success?

VB: That there are no rich.

There's actually enough for everybody.

We don't have the stratified, fragmented, disparate and desperate society we have now. The things that we are fighting so hard for, that seem so impossible, have become real. There is quality health care, housing, and food for all; there is clean air and water. These material conditions are understood to be basic rights. These social policies, that are radical now, become agreed upon and expected, like brushing your teeth before bed.

MG: Any other thoughts you’d like to share today?

VB: Whatever we do, I’d like us to be kinder and more understanding of ourselves and each other in the process.

We're really hard on ourselves in the US Left. We're really, really hard on failures. We feel so much responsibility for getting it right. We feel so burdened. And I get it. I get why. We're up against authoritarianism. We're up against a Right that wants to take us out. We really feel beholden to our vision for human dignity and care and compassion. Sometimes what that means is if we fail, we just self-flagellate ourselves brutally.

Coming out of the pandemic, everybody is still in grief and exhausted. It's really hard to ask people to envision a world where things are better 10, 15, 20 years down the line when we're stuck in what feels like the muck right now.

Structurally speaking, a lot of our gains have been dismantled. We’re dealing with movement-level heartbreak and sadness and grief while trying to keep up high levels of organizing. It's an intense time in the world. It’s a big deal to ask people, in the midst of all of this, to keep imagining and trying and playing and collaborating — to ask people to set aside their egos and sense that it’s all on them.

The structures that we're trying to change and dismantle in our work organizing the rich are about shifting the very nature of wealth as we know it. This is hard work, partly because, especially in the US, we don't know of and see alternative economic and social structures that are at scale. For many of us, we really have to build this thing — this cross-class multiracial movement, this solidarity economy, this just transition — and trust that it’s going to be a thing without ever having seen it happen, without knowing it’s possible. That's a lot to ask people who just survived a global pandemic and are just trying to live. It’s the right ask and it’s a big one.

—-----

Wow. Thank you Vini.

If you enjoyed this interview, please press the heart below, share it with others and add your comments, feedback and reflections below. Vini and I would love to know what resonated, what didn’t, and what questions you might have.

Thank you to Vini, Barni Qaasim and Cynthia Williams for their help with editing.

Solidaire was founded in 2012, after Occupy. In its first many years, a big part of Solidaire’s work was as a rapid response vehicle for funding progressive and Left movements.

In my experience as a fundraiser, many publicly proclaimed matches are ones where the wealthy donor or foundation is going to give the money no matter what. They are often matches in name only, used to generate energy and enthusiasm and urgency for a fundraising campaign. They are matches where the organization is driving the strategy and strategically leveraging a donation. These are matches that are different from the one’s Vini is referring to above, where a wealthy donor is using their donation as a way to get a group to do what they want.

Let me join the chorus of praise for this interview. You and Vini have packaged a vision of donor organizing that crisp, clear, powerful and persuasive. It’s a terrific summary of the lessons Solidaire has learned in its relatively short existence and their application to its next steps. I’ve shared it with a number of folks outside the network, and the feedback has been quite positive. Thank you both for putting this out there for us to digest.