What a rough last week. I want to write to you about this election, but I’m not there yet. I’m going to take time to be family and friends, feel the loss, celebrate the wins, and reflect. I hope you can too. Sending you much love in these sobering times.

What I am going to do is share the second part of my interview from 2023 with Leah Hunt Hendrix. I’ve been sitting on it long enough, unsure when to post in the midst of this election season. I will share it now, both because the topic of rebuilding the labor movement is as timely as ever, and because it gives me a chance to invite you to join me at an election debrief that Leah is organizing with her current project Democracy Takes Work. Invite below:

‘What just happened? And what can we do to defend, and even rebuild, the labor movement as a bulwark against authoritarianism? Join us Monday, November 11th at 4pm ET for a conversation with labor and philanthropic leaders to make sense of this moment. We’ll hear from Gwen Mills, International President of UNITE HERE, Randi Weingarten, President of the American Federation of Teachers, Jenn Epps, Executive Director of the LIFT Fund, Deb Axt of the JPB Foundation, and additional labor and movement leaders.’ [The webinar is now past, but you can view the recording here.]

Last summer I published the first part of my interview with Leah Hunt Hendrix, co-founder of Solidaire and Way to Win, and co-author of the recent book, Solidarity.

In the second half, Leah talks about her two priorities for organizing the rich, the traps and tensions of modern day philanthropy, and why even wealthy progressives often shy away from funding worker organizing. Towards the end, in one of my favorite parts, Leah speaks to the challenges of being vocal and visible as a wealthy person with social justice values.

Since our conversation, Leah has taken these ideas and run with them. She has become Senior Advisor to a new project called Democracy Takes Work (DTW), a cross-donor-network collaboration, started by the Democracy Alliance and including Solidaire Network, Way to Win, and Movement Voter Project.

As always, this interview has been edited for content and clarity. Please remember, this conversation was a year and a half ago, and reflects the reality at the time.

Mike: If you could identify a few priorities for progressive wealthy people organizing in the next five years, what would they be?

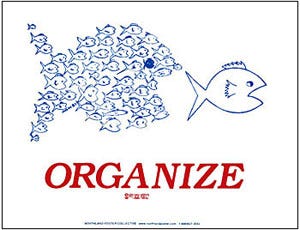

Leah: For me, the drama of politics is about organized people in opposition to organized money. Part of our work in the progressive donor world is to organize money behind organized people1 or, to say it differently, divert financial resources from the ruling class towards the multiracial working class so that they can build a better society for all.

I would argue that progressive wealthy people should focus on two key priorities, the two pillars that uphold our social and economic system: one priority should be rebuilding the labor movement, which is the institutional representation of the working class. If that pillar is strong, benefits will flow to all of society more broadly. And the flip side of that coin is restraining corporate power, which is the vehicle that endows the few, the elite.

It was labor unions that won the weekend, the 8-hour work day, and child labor protections in the wake of the Industrial Revolution. Labor unions benefit all of society because they expand the safety net, they fight for standards and conditions that impact everyone, and they give a political voice to the working class, which is the majority of society. When the labor movement was at its height in the mid-20th century America had the strongest middle class, and the lowest level of economic inequality, we've ever had.

But exactly because of its power, the labor movement has been under attack. Companies have waged fierce anti-union campaigns, and our labor laws don’t provide sufficient support for workers trying to unionize. The right has passed so-called “right to work” laws in many states making it harder for unions to get funding to organize. Labor density (the percentage of workers in unions) has decreased from almost 35% in the 1950s to about 10% today. Nevertheless, we are in a movement moment, and people around the country have been taking steps to build new unions in recent years, such as at Starbucks, Amazon and Trader Joe’s.

One reason I think unions are so important, as opposed to just funding traditional non-profits, is that philanthropy is riven by a fundamental contradiction: while it often says its aim is to help those with less, it's the product of amassed wealth, made on the backs of underpaid workers.

Wealthy philanthropists might genuinely want a better world, but most waver in their belief that the working class should actually have powerful institutions that can challenge the status quo [or their profit margins]. For this reason, philanthropy can’t build the world we need. The interests of wealthy donors are almost always in opposition to pro-redistribution anti-inequality movements and policies, and the fickleness and ability for these donors to control or withdraw their support creates too great of an obstacle to really tackle questions of economic inequality head on.

Rebuilding the labor movement is crucial because it’s an institution that is self-funding [funded by its members’ dues] and can wield power independently of donors and the owning class. There is a role for people in philanthropy to help grow the labor movement, help unorganized workers get organized, support strike funds, provide legal defense, or advocate for pro-worker and pro-union policies. But once unions are established they no longer need significant grant-funding2, and that’s a really good thing. Through labor unions, working class people can fight for what they need, without being dependent on the benevolence of wealthy donors. Self-funded and member-funded poor and working class organizations are the way out of the paradox of philanthropy.

I should acknowledge that the labor movement has had a lot of problems: racism, sexism, corruption. But it doesn't have to be that way. There have been a lot of changes in the field over the past several decades, and a recognition that women of color are in many ways at the center of what we mean by “the working class.” They are the majority of domestic workers, service workers, restaurant workers, all of whom have been getting organized. There are also reform movements within major unions like the Teamsters and United Auto Workers. Philanthropy can play a meaningful role in these efforts. For example, I’ve been working for the past several years with Teamsters for a Democratic Union, which is a grassroots group of Teamsters who have fought to make the union more democratic and representative.

To my second priority, we have to find ways not only to build up workers’ power but also restrain corporate power. Efforts like reviving anti-trust laws, or fighting for progressive taxation, may seem wonky but are crucial to the fundamental balance of economic and political power in this country.

The Chamber of Commerce is one of the biggest obstacles to progressive organizing in the US. For example, the Chamber of Commerce sued the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau - the agency created by Elizabeth Warren to protect consumers - in an attempt to declare it unconstitutional. The Chamber also ran ads against the El Paso Climate Charter ballot initiative. Over and over, you’ll find them opposing the public interest. One organization I support is Revolving Door Project, which has a tiny budget, but punches far above its weight to ensure that people appointed to federal agencies aren’t just representatives of big corporations who will bend the rules for private gain, but instead, are truly public servants who will fight for the public good.

Mike: I love those priorities! Are there more examples of how you’re helping progressive philanthropy back the labor movement?

Leah: For the past several years, I’ve been moving resources through Way to Win with a three-part funding strategy.

One is to fund the grassroots organizing to rebuild the labor movement, like the Amazon Labor Union or Teamsters for a Democratic Union, or the Emergency Workplace Organizing Committee - groups providing support for worker organizing. We need to see union density increase in the U.S. so that’s become my north star.

Second is a media strategy to develop a narrative that is pro worker, to document successes and build a sense that workers can organize and win. More Perfect Union is our main grant around that right now.

The third part is a political strategy, to ensure that Congress and people with political power are on the side of workers.

For example, when the rail strike happened in 2022, Biden, who was supposed to be the most pro-labor president in decades, ended up siding with the railroad corporation because he was scared a strike would hurt the economy. The workers just wanted six paid sick days but Biden crushed their chance of winning. We need to make sure that when workers strike, they have allies in political office saying, “These workers have a right to strike. They deserve the benefits they’re fighting for. They're essential workers and we stand with them.” And then as we get into 2024, we need to make sure worker power/a strong labor movement is something Democrats are running on, and then in 2025, we ultimately need labor reform at the national level.

Some foundations have been funding worker organizing; there's a little bit of support for pro-worker and progressive media. But I think it’s important to fund a political strategy to ensure that the Democratic Party becomes the party of the multiracial working class. Because as the Democratic party has become more elite, Republicans have tried to claim the mantle as representative of the working class, even though this is disingenuous. We can help shift the politics of the Democratic Party by funding working class candidates who are running for office, such as through the Working Families Party, but also through lobbying and advocacy.

I like to use a framework of: the grassroots outside, the political inside, and then the media to overlay the narrative. It’s probably a framework that could apply to a lot of different issues.3

Mike: Thank you. I'm excited about every piece of that. What is going well in moving wealthy people and wealthy institutions toward those goals, and what are the blocks that you run into?

Leah: There are not a lot of donors in this space. I think that’s probably a legacy of the age-old battle between the working class and the owning class, and the ongoing reality that philanthropy is the legacy of the owning class. People who’ve made millions or billions often did that in opposition to the demands of labor, by driving down labor costs [ie decreasing wages and benefits while increasing automation]. For younger people in wealthy families, who may not have made the money themselves, I think the obstacle is often that they don’t have a positive personal relationship or experience with unions.

There’s a gulf between the worlds of philanthropy and unions. And since unions can’t take philanthropic dollars directly since they are not 501c3’s, that gulf has been slow to be bridged. However, as I mentioned, there are ways for philanthropy to support the project of rebuilding and strengthening the labor movement through 501c3s and those resources could actually be crucial.

I do think the anti-monopoly movement has gotten more popular, and more foundations like Omidyar and the Sandler Foundation have become involved, which is fantastic. But we need a lot more education in philanthropy about how corporate power is often part of what’s eroding the public goods that would benefit us all.

Mike: Just to underline the point you made, I grew up disconnected from unions. My introduction to activism came through nonprofits and social justice philanthropy - worlds quite separate from the labor movement. From what I’ve seen, many progressives from wealthy backgrounds share this experience. We either superficially support organized labor but have little real relationship, or we've absorbed the anti-union attitudes that are so common in professional and wealthy circles. Or both! What are your thoughts on how to get more wealthy folks involved and supporting these efforts?

Leah: I think we need to proactively organize a cohort of funders to go through a process together that would involve going to union rallies, having one on ones with workers and with labor leaders, and studying the history of the labor movement. It was labor that won so much of the New Deal and so many of the big social programs we got in the mid 1900’s. We need to start a process of deep education on this topic.

Mike: What moved you onto this track?

Leah: Much of it was my concern that there's no ideal place to end up in terms of the relationship between philanthropy and nonprofits. There's just no way out of the power paradox. Either non profits don't have sufficient power OR they have power, but then they're tied to the interests of the donor class.

Working class led organizations that are funded directly by their members have such a better form of accountability. And while the labor model isn’t perfect, at least there is a form of internal democracy. They are directly accountable to their members, because that’s who they’re funded by.

I’m interested in the Working Families Party model of having grassroots community organizations and labor on a governing committee together.

There could be other ways to structure organizations so they are accountable to the members they're trying to serve, even while they take money from wealthy supporters at the same time. There's no perfect situation. There will always be internal conflicts. But it’s better when those can be hashed out democratically instead of decided by the donors.

Mike: What are the relevant pieces of political education that you think are needed within progressive donor networks to strengthen solidarity and support for worker organizing efforts?

Leah: People need to have an analysis of the bases of power in society and the fulcrums that can move those. As I said, unions can be a source of real power. So can the Chamber of Commerce. So can any major industry or interest group lobby. On any given issue, you need to start with a power analysis.

I also think about the movement ecosystem work that has been developed by Paul and Mark Engler and Carlos Saavedra, and taught through the Momentum Community and its workshops. I would run wealthy progressives through those trainings a million times.

Then we need history - history of the labor movement, of right wing philanthropy, of how any major social policy was passed. People need a real understanding of how large scale change takes place. And we can’t be afraid of looking at the role of politics and policy, and getting political.

Mike: One thing I've been asking people is for their 50 or 150 year vision of success for engaging wealthy people in the generational challenges that we're taking on. What are your hopes for what that could look like in the next 50 years or 150 years?

Leah: In 50 or 150 years, I hope we have a true democracy, not one that is governed by the wealthy. I hope that we’ve been able to redistribute all the amazing tools and resources we have, so that everyone has enough, rather than so much being concentrated in the hands of a few. We are so close to becoming an oligarchy run by Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos and the Murdoch family. I hope we move away from that brink.

Mike: I imagine it’s not so easy to talk about, but are there challenges being a wealthy person who's so visible and is leading this work in big ways? I don't think most people really understand the challenges of the type of visible leadership you’ve taken on.

Leah: I've taken some risks in being visible in hopes that it would inspire other people who have this class background to do something similar.

But journalists love to flatten it, make it about the “rich liberal girl,” make it gossipy. During Occupy I spent a lot of time with a journalist to try to tell the story of why a wealthy person should stand with Occupy Wall Street. Then the editor slapped on “Occupy’s Heiress” as the title, which was embarrassing. I was profiled in a book more recently, hoping the author would focus on my work, but a lot of what was written tried to make me seem like a hypocrite, talking about the working class while drinking a matcha latte.

This makes me tear up a bit! It feels vulnerable. But I want people to know that if you have inherited wealth, you can do more than just buy fancy things. And I do hear about positive ripple effects from the articles I’ve done, so I think telling our stories is still worth the risks.

Mike: I have so much respect for you Leah, and for the stands you’ve taken. And I've seen over and over again how our [wealthy] people who take stands get patronized. Especially if you’re young or a woman, you get patronized and portrayed to be naive or vapid. That's bullshit. I hate it. The tears are welcome. What you have to say here is important.

Leah: Thank you. There are not a lot of people you can talk to about this stuff. I never want these challenges to be construed as a “woe is me” story, where I’m looking for pity.

A frustration I sometimes have is that if you go public as a rich person about the work you’ve done helping fund movements, you can get smeared by both the right and the left. But if you don’t talk about it, then a lot of work is behind the scenes without people really understanding what went into it.

And you can get kind of pigeonholed. When people call, it’s usually about money. When my older sister dabbled in philanthropy, she told me “Leah, don't get involved in philanthropy. You're not that level of wealthy.” And I wouldn't have, except at Occupy I felt requested to use my class privilege to support the movement. But it really locked me into this ‘wealthy person movement fundraiser’ identity. I have a PhD from Princeton but people are more interested in my access to wealth than my ideas.

That's a smattering of the challenges. If I'm totally honest, it’s often been quite hard to be in this role. I'm curious what might feel more rewarding in my next phase. I love the political education stuff we've talked about. Our conversation is reminding me that I love that and am good at it. Maybe there's something there.

Mike: Thank you for sharing all that. We have to get better as a movement at supporting wealthy people to take the risks that you've taken. The big economic transition that we need, the working class power we need to win, is going to take more of us being as bold as you've been. And we don't yet know how to hold and support wealthy people consistently when they do that.

What would you say to younger wealthy folks who are inspired by what you’ve done? How do we hold them with more care?

Leah: I would say in the Solidaire early days, having a small crew that really knew each other felt really good. We could talk about the hard things together. So having your own little cohort to go through this all with is what I would advise anybody. Join a community4, find people who can support and challenge you, and if the ones that exist don’t work for you, start one.5 Start by reading a few books together, try funding a few projects together. Just be in community, and don’t worry about being perfect. There will be contradictions, but we can all just do the best we can.

Mike: That tracks with my experience too. Having a small crew you can share everything with is so important.

Thank you Leah for taking the time to talk.

I love this phrase, “Organize money behind organized people.” It sounds so good. But I don’t totally get it. Isn’t organizing money about organizing people?…in this case the owning or managerial class people who control the money? Are we using the words ‘organize money’ as shorthand for ‘organizing the rich’? I think so? Maybe. Thoughts for future conversations.

In case it’s not clear, Leah absolutely believes that there is a role for foundations and wealthy people to financially support labor. That is the fundamental premise of Democracy Takes Work. And, at the same time, it’s so helpful that labor, because of membership dues, is not dependent on philanthropy.

Yes! Let’s help all the wealthy people we know find community and a political home. Not sure where to start? I made this Rich People Organizing Cheat Sheet to help wealthy folks new to this world find a home base. It’s a work-in-progress and I’d love to know what you think.

A message I learned early on, from Resource Generation and many others, was “Discourage wealthy people from starting new organizations!” It remains a necessary counter to the common thought that, armed with our many degrees, resources and connections, we [the rich] are uniquely and best suited to lead on any given issue or topic. Instead I was taught to encourage wealthy people to join established projects and learn how to be reliable participants and contributors. I still think this is good advice! And, there are many examples of projects started primarily by wealthy people (including Solidaire and this one, Organize the Rich) that I absolutely am glad exist. All to say, I think of this message and hold this tension as I read Leah’s suggestion.

Something you may be interested in exploring: Funders for a Just Economy has a strategic focus on funder organizing to better resource worker power building. I'm sure Leanne would welcome a conversation.