I was sitting in a meeting the other day at Fruitvale Station in Oakland, CA, getting to know a colleague I’d only met over zoom. She is a White woman who grew up middle class and is now rich. She is a leader, curious, passionate and brave. I enjoyed our lunch and conversation.

She was mentioning the Substack and told me how she’s uncomfortable with the name of it, Organize the Rich. There was something about it that she didn’t like.

I guessed that it’s probably the ‘rich’ part because that term is often used as a put-down. “Eat the rich”, “rich kid”, “richie rich”, none of them are positive.

She agreed. It wasn’t a term she particularly wanted to be associated with.

After a few more minutes she shared a new thought. She commented that her discomfort with the term “the rich” reminded her of the idea of “white fragility”, coined by Robin DiAngelo in 2011. The general idea is that white people often get defensive in conversations where their ideas about race and racism are challenged, particularly when they feel implicated in white supremacy. I had never thought of that connection before, how rich people have our own version of, in this case, class fragility. I liked seeing in real time how the title of the substack was both uncomfortable, agitational and leading to new ideas for both of us.

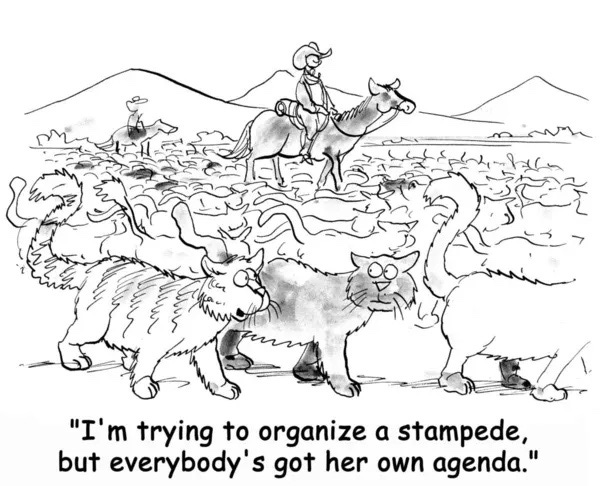

She also talked about the word “organizing” and how it makes her feel like she’s been herded like cats. I nodded. There’s a lot of truth in what she was saying. Certainly I have spent many days fundraising or organizing the rich, and feeling like I’m herding cats, really wealthy cats who are constantly on vacation.

She went on to share that if I wanted to engage wealthy people in this conversation, the name of the Substack might be an impediment.

I think she’s right. Some wealthy people might be turned off at first. And, I’ve realized, I’m ok with that.

The conversation I want to have and the audience I am writing for is (you!) a cross-class community of people.

I am not writing primarily for the rich. It is one of the three audiences I have in mind.

In case you're curious, those audiences are middle class professionals who engage and advise wealthy people around progressive values; poor, working and middle class progressive movement leaders; and liberal to left wealthy people.

The conversation made me want to write a little about the terms I use when describing people with financial wealth, as there are a few different things going on.

Often, I talk about a person’s current class position or their class background using terms like owning class, managerial or professional middle class, middle or working class, and poor. These terms are about a person’s relationship to the means of production in a capitalist society.1 I think this is a crucial way to understand our society, our capitalist economy and the different roles we can play in transforming our world.

I also use terms like ‘the rich’, ‘rich people’ or ‘wealthy people’. I like that these words are commonly used and easily understood.

In non-profits, philanthropy and the financial industry we can be quite precious and opaque about how we talk about the rich. For good reason, we often treat the wealthy like skittish deer that will flee at the slightest whiff of danger. We try to avoid any hint of discomfort by using descriptors, like ‘donor’ and ‘high net wealth’, ‘wealth holders’ and ‘high capacity’.

I like contradicting that culture of slipperiness around class by using a term like “the rich”. People know what that means. It has a flavor of class struggle that I enjoy. I think a hint of class conflict can be useful in a society that tries to pretend that everyone’s interests align with the owning class. Terms like ‘the rich’ challenge the ability of the owning class to define and control the conversation, which I hope pairs nicely with the potentially surprising message that we need to organize them with love and rigor, like everyone else. Class conflict + love + rigor. That’s a bit of the honest, kind and not particularly careful or precious tone that I’m going for.

When I am writing primarily for an owning class audience, I think the term ‘people with wealth’ can be useful. We are ‘people’ first, and then we have financial wealth. We are not necessarily wealthy in many other ways – in kindness, community, and care. In my experience, ‘people with wealth’ can be a fairly innocuous term for a wide ranging set of rich people, while still being explicit about the money.

One term that bugs the shit out of me as shorthand for the rich is ‘donor’. It really has gotten under my skin! I mean, ok, I was brought up to understand myself as a ‘donor organizer’. I have an abiding appreciation of the history2 and the usefulness of the term. It’s short! It’s unthreatening! It’s even kind of cool! I mean, really, what’s there to hate on?

Well, when ‘donor’ is used as shorthand for the rich, it can hide the fact that most donors, and the most generous donors, are poor and working class people (remittances to the Global South being one of many examples). If we forget this reality, then our fundraising strategies too quickly center the rich in unhealthy ways. My other primary concern is that we limit and constrain our work with wealthy people by solely focusing on making them better donors.3 I want progressive movements helping rich people look at the whole picture of their lives, including all their $$$, not just the pennies they’ve put aside for their philanthropy. I know and have seen ‘donor organizing’ be a gateway to that larger transformative work. I’ve also experienced it as a term and practice with a limited long-term vision, that ends up being unable or unwilling to push wealthy people to look at their full financial picture and their personal stake.

I was talking to Taj James the other day. In his work with Full Spectrum Capital Partners, they use the term “capital stewards” to include both people with wealth as well as the many professionals, such as foundation executives and investment professionals, who are responsible for managing wealth. To be honest, I had heard him use that term before and had always rolled my eyes (only in my mind I hope). I thought it was one more class evasive label meant to make the wealthy more comfortable. My assumption was wrong. In our conversation, he described using that phrase to encourage people to understand that the money is not their own, and that it is their responsibility to manage it thoughtfully and in alignment with the collective good (my words, not his). A different term and approach than what I’m used to, and I found it fascinating to learn about why he and his team have made the language choices that they have.

—-----------

I don’t think there is a right or wrong term to use when describing the rich. I can imagine myself employing the classic conservative label of “job creator” depending on who I was trying to organize.

I want my language to be accessible, engaging, and agitational, while also modeling my values. I want us all to be creative and flexible with our words, and in more open conversation about why we use them, especially around taboo subjects like class and money. I’m curious to experiment on this Substack and learn in the process.

I am ok if some wealthy people are uncomfortable with the title. My experience at Resource Generation was that the more bold and clear we became with our mission, vision and values, the more we grew our base. For every young wealthy person who walked away, there were 3 or 4 or 5 drawn to us by the honest and unique way we talked about class, wealth and social change.

I am hoping the same thing happens here. Sure some wealthy people will be turned off by the title, and my bet is that many more will be drawn to an interesting, honest, not too careful conversation about their role in building a healthy, just world.

And, just maybe, they’ll come to appreciate that while being organized can sometimes feel like herding cats, it’s also a precious gift and invitation.

—----------

What terms do you use in your work with the rich? Why?

I’d be curious to learn how you navigate language around class and money in your life and work.

My quick understanding of the primary class roles in capitalism are: Poor people are used as excess labor so that working class wages stay low. The working class make all the shit and do all the shit that keeps society functioning and generates the profits for the owning class. The middle class are a better-paid (bribed) part of the working class, who help with the smooth functioning of capitalism, making it easier for the owning class to extract profit from workers and the planet. The managerial class are the well paid professionals in the middle class that work closest with the owning class. They are almost always not unionized and the part of the middle class most closely aligned with the interests of the rich (in part because they often own property and have money in the stock market). The owning class extracts wealth from workers and the planet by any means necessary.

Anne and Christopher Ellinger coined the term ‘donor organizing’ in the 1980’s and 90’s. “For years, we worked with the staff and donor activists of the Funding Exchange network to shift their thinking away from seeing donors simply as people who gave money, to seeing donors as people to fully engage as part of the community working for change. We termed the work “donor organizing.” More to come on this important history in future posts.

What do I mean by a “better donor”? This is the vital decades-old work of social justice philanthropy. For me, becoming a ‘better donor’ means learning from these social justice philanthropy principles, along with wisdom gathered in places like the Decolonizing Wealth Toolkit, this Just Transitions guide to philanthropic transformation from Justice Funders, trust-based philanthropy, and electoral funding shops like Way to Win, Movement Voter Project, Groundswell Action, Democracy Alliance, and Committee on States, to name a few.

I appreciate this framing especially as someone who has organized rich people to be donors but also impacted community to join membership organizations or be monthly donors. The conversations with retired teachers on fixed income and with rich folks have many parallels and some departures but they're all donors. The agitations each need are also different and often have to do with language. This is why I often ask folks to give an amount that is meaningful to them. While some rich people may not feel as implicated by those words; its a good starting point for both in a way that doesn't alienate and is accessible.

I appreciate that you allow for the provocation of the language you've chosen to stand, while also demonstrating curiosity about the reasons why folks feel provoked by this language. These conversations allow us to move beyond the impulse of discomfort and toward a greater understanding — of ourselves and each other.

Having a long history in narrative strategy and strategic communications, I often tell people that the language we use is less important than the meanings (plural!) we ascribe to that language, because that's where the deeper work lies, and that instead of arguing about language (thereby, remaining surface-level), we might find that we have more alignment at the level of meaning if only we were to ask a question rather than make and stand by our assumptions.