When I was 23, Holmes Hummel told me that we are all taught to compare up. I was sitting in a living room in Bernal Heights, at a Resource Generation local dinner for young people with wealth. We were talking about money, class and how to leverage our resources for social change.

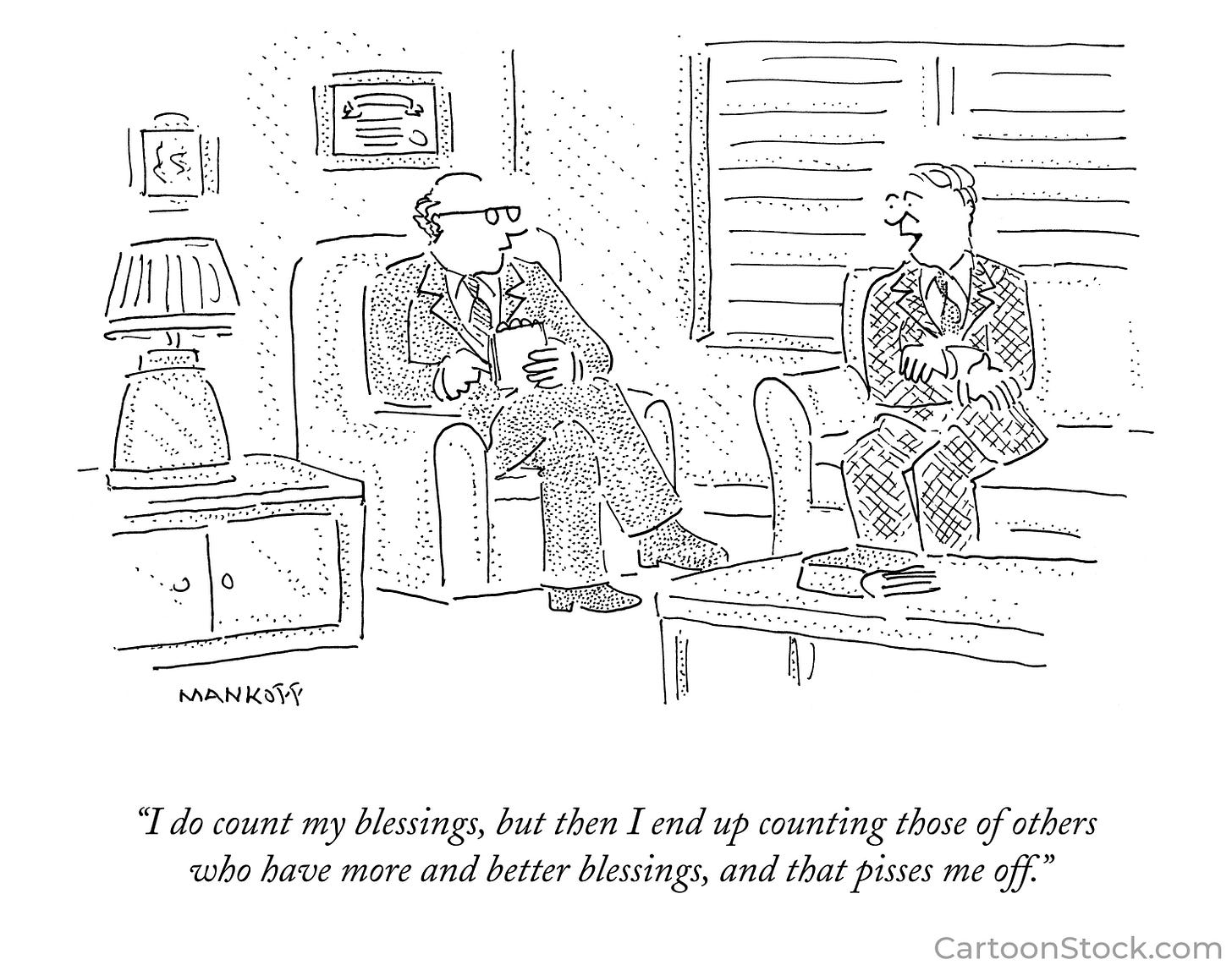

Always compare up. I’ve kept that phrase in my head ever since, sharing it with others whenever I can.

What did Holmes mean? They meant that, in our class-based society, we are encouraged over and over to compare ourselves to those that are wealthier and farther up the economic ladder.

Holmes wasn’t sharing this message so that we could agree with it or act on it. Holmes was attempting to inoculate us against this common tendency.

—--------------

I’ve always gone to expensive private schools. In those spaces, it was easy for me to compare up to the kid in my class with an elevator in his house, or the great grandchild of a famous Robber Baron, and think “I’m not so rich.” I didn’t grow up with a second home. My parents didn’t buy me a car when I turned 16.

My Dad was an architect who generally worked for people wealthier than him, designing beautiful and expensive Bay Area homes. Early in my life, my Mom took care of me and my two siblings, while at the same time caring for my grandma as she developed and died from Alzheimers. I wasn’t sure what upper middle class meant, and it seemed like it could be a fair descriptor of my family’s class position.

As I grew older, I noticed other facts about my life that made it all more complicated. I heard stories of grandparents and great grandparents who owned businesses, lived in fancy neighborhoods and studied in Europe when they were young. My parents both went to Stanford. I had a trust fund from birth, set up by my Nanna, to pay for my private school education. Me and my wife’s parents gave us money to help buy our house in Oakland.

The truth is that we were and are part of the top 1% of wealth holders in the world (even while we are “only” in the top 5% of wealth holders in the US). And, while several of my grandparents came from more traditionally owning class families, I’ve lived my life with a solid foot in both the middle and owning class. Depending on the day and who I am hanging out with, whether I am talking with my friend struggling to pay rent after a breakup or my friend whose Mom recently told her she has $300 million dollars, I can feel very differently about my class position.

And if I step back, by almost any measure, we are financially rich, with a net worth, including our house, of over a million dollars. Rich enough to afford a home in Oakland, an electric car and a vacation to Japan this Spring. Rich enough to have more than we need.

Yet, I continue to be dogged by insecurity around our finances. As Astra Taylor, co-founder of the Debt Collective, writes so brilliantly in her recent Op-ed in the NY Times and her book on the same topic, we are all suffering from a universal and intensifying manufactured insecurity. “The ways we structure our societies could make us more secure; the way we structure it now makes us less so. I call this “manufactured insecurity.” Manufactured insecurity encourages us to amass money and objects as surrogates for the kinds of security that cannot actually be commodified — connection, meaning, purpose, contentment, safety, self-esteem, dignity and respect — but which can only truly be found in community with others.”

I’d like to put forward that one of the most successful advertising slogans of manufactured insecurity is “Always compare up.” It’s an idea that often leads me to both want more, and downplay how much I already have. What I’ve always appreciated about Holmes’ comment is the implicit warning to avoid the temptation to play down my actual wealth and power. It reminds me to look down the class ladder, not just up. It helps me notice how much I have, rather than focusing on what I don’t. And that’s important. Because Compare Up is based on the idea that those with more necessarily have better lives. And what I’ve seen over and over is the fallacy of that idea.

Growing up, the kids from wealthier families than mine always seemed to have bigger struggles. They were left alone more, and had greater expectations put on them. They often had major substance abuse and self-esteem issues. None of these are unique to the rich and yet, the lonely rich kid is a familiar archetype for a reason. I think the impact and harshness of upward mobility – the competition, isolation, assimilation and pretense – is often underestimated.

How does this all relate to organizing the rich? I’ve found that wealthy people tend to minimize their wealth and power by comparing up, distancing ourselves from those ‘really rich’ people. We can justify holding on to almost any amount of money by noticing the neighbor who has more. When we dodge looking honestly at our wealth and power, then the rat race continues unchecked. The societal message telling us we’re not enough, don’t have enough, and need more to stay safe or live a good life, persists. That voice is a mean companion.

Noticing that those messages are not mine, but the voice of the broken economic system we live in, has always been helpful and reassuring.

Maybe Holmes words are a helpful reminder for you too.

thanks Mike! Really good guidance.... and reminder. And I think that one "compares" in the direction of those around.... I think it is more comfortable to compare up (i know, that's your point) than to "compare down" --because then, yikes, the lack of fairness is startling. And thanks for the term "manufactured insecurity" -- keep up the good work! on one of my fave topics! xoxo